Are there Habitable Planets?

The following question came in as part of a response to our Spacing Out Newsletter survey: “Are there any planets we've seen that would be more habitable than Earth, or at least have any cool quirks if we were to settle them such as Earth's unique solar eclipse?”

When I first read this question, I was totally going to give a short, succinct answer, but then my brain started going “ooh, but you could mention this!” and “oh, what about this!” and, well, now here we are.

The short, succinct answer to this question is: we have no idea. We don’t know if any of the planets we’ve seen are more habitable than Earth (we know most definitely are not), but the fun comes in answering why we don’t know, and whether we’ll be able to know soon (I haven’t forgotten the quirks part of the question, I promise. I’ll get to that later).

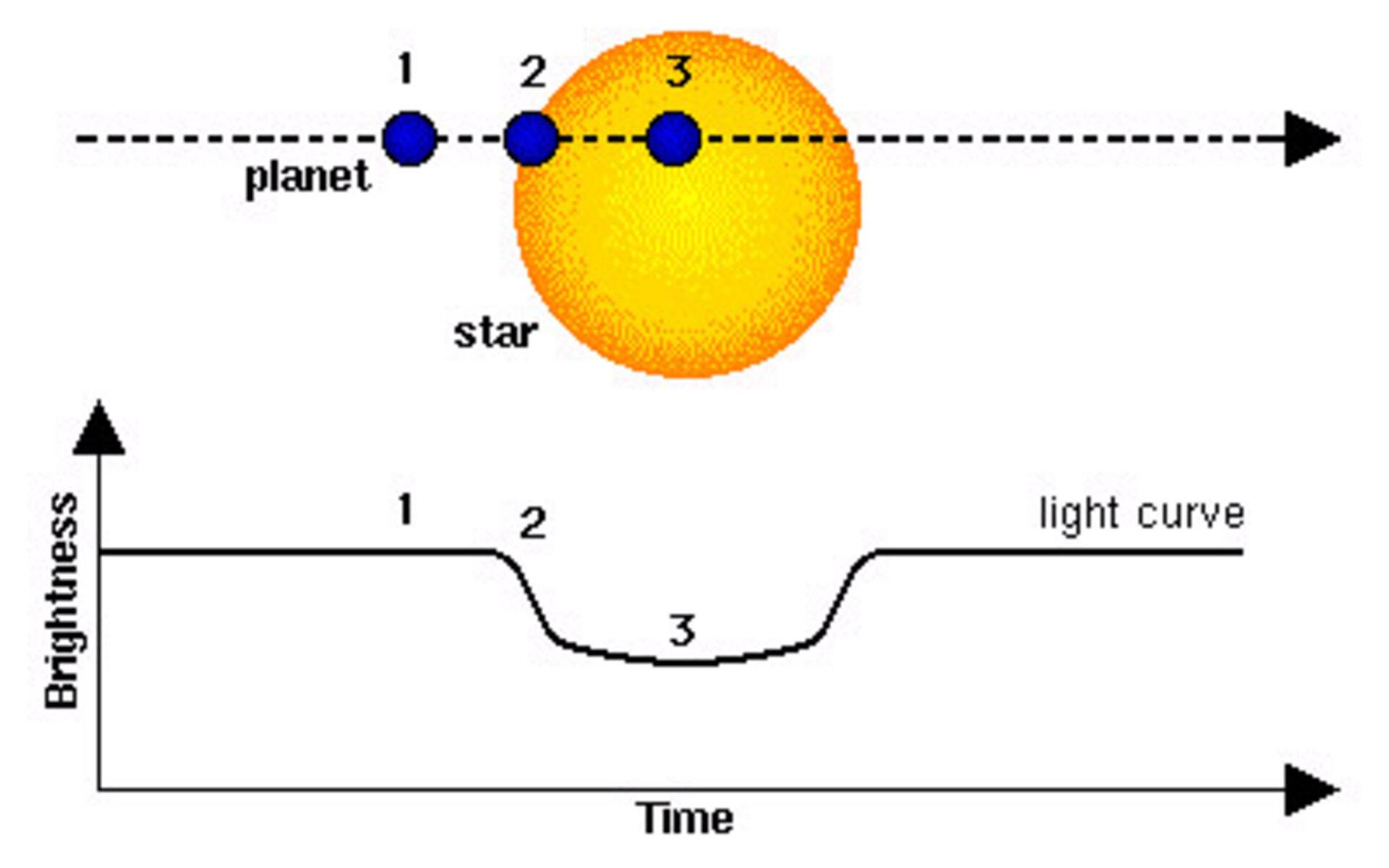

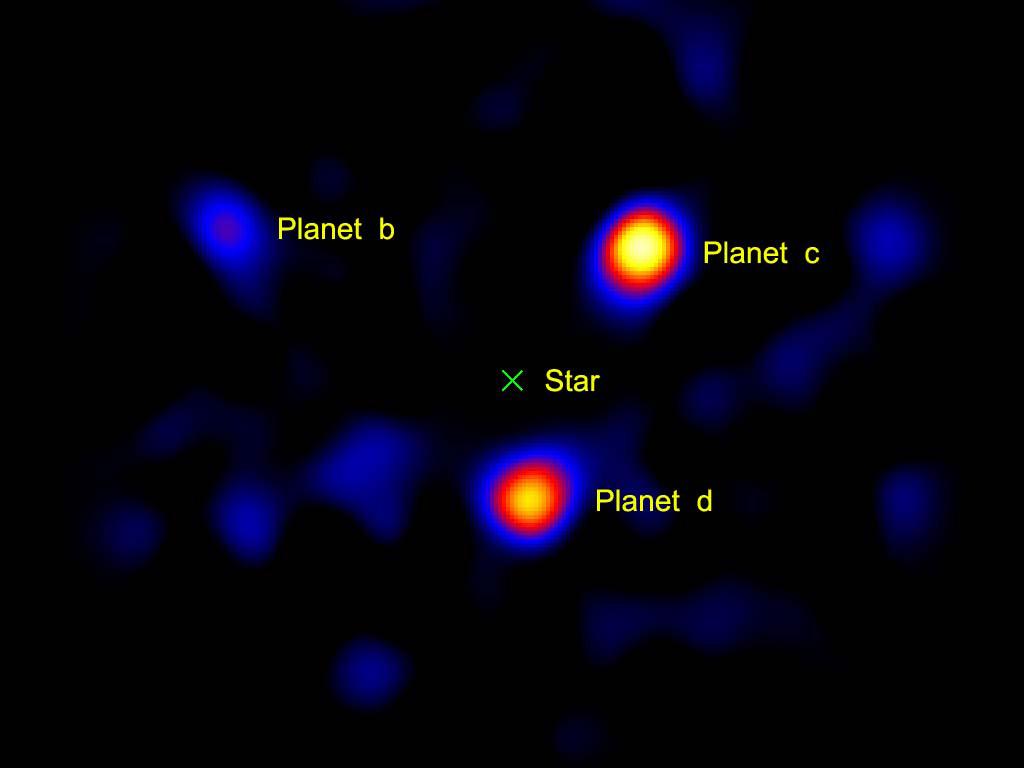

Let’s talk a little about how we find exoplanets. There are a few tried-and-true ways to do so, some of which will get you more bang for your buck than others. Sometimes, mostly when a planet is large and far from its star, we can image it directly, which we (sensibly) call direct imaging. Sometimes the geometry is just right that the light from background stars can be bent by the gravity of a star and its planets, letting us know the planets are there. We call this gravitational lensing because the gravity is bending the light the way a lens does when light passes through a telescope. Sometimes we can detect the planet pulling on the star with its gravity, making the star wobble. As the star wobbles towards and then away from us, we can detect the motion, and we call this the radial velocity method. Mostly we find them when a planet passes directly in front of its star, blocking some of the star’s light. The passage in front of the star is called a transit, so this is called the transit method.

While this is not an exhaustive list of detection methods, they have something in common—all of these methods are great at telling you a planet is there, and roughly how big it is, and most will give you an idea of what the planet’s orbit looks like and maybe its mass. None of that will tell you what the planet’s surface looks like.

Imagine for a moment that you’re an alien, and you’re doing exoplanet research on your alien homeworld and you’ve got this kind of data for a mid-sized yellow star about 30,000 light years from the galactic center (I’m talking about the Sun, but you’re an alien, so you don’t know that). You might be able to find out that this star has three decently-sized rocky worlds ranging from roughly 75-150 million miles, or whatever you use as distance measurements, from the star. That’s potentially exciting, since just based on what you know, any one of those worlds could theoretically, maybe, possibly, have the right conditions to support life.

But that’s all you know. You can’t tell that one of those planets has had the greenhouse effect go nuts and turn its surface into a boiling hellscape (Venus), or that one barely has any atmosphere and is a frigid desert (Mars), or that one has a pleasant atmosphere and huge oceans and grasslands and forests and towns and cities and elephants and bears and people (come on, you know which one I’m talking about).

So we don’t know what the surfaces of any of these exoplanets look like yet. Even if we’re pretty sure a planet is rocky and the right distance from its star to be able to have liquid water on its surface (which we call the habitable zone) we don’t know if it’s an airless surface like Mercury, a frozen wasteland like Mars, a scorching misery like Venus, or a relative paradise like Earth.

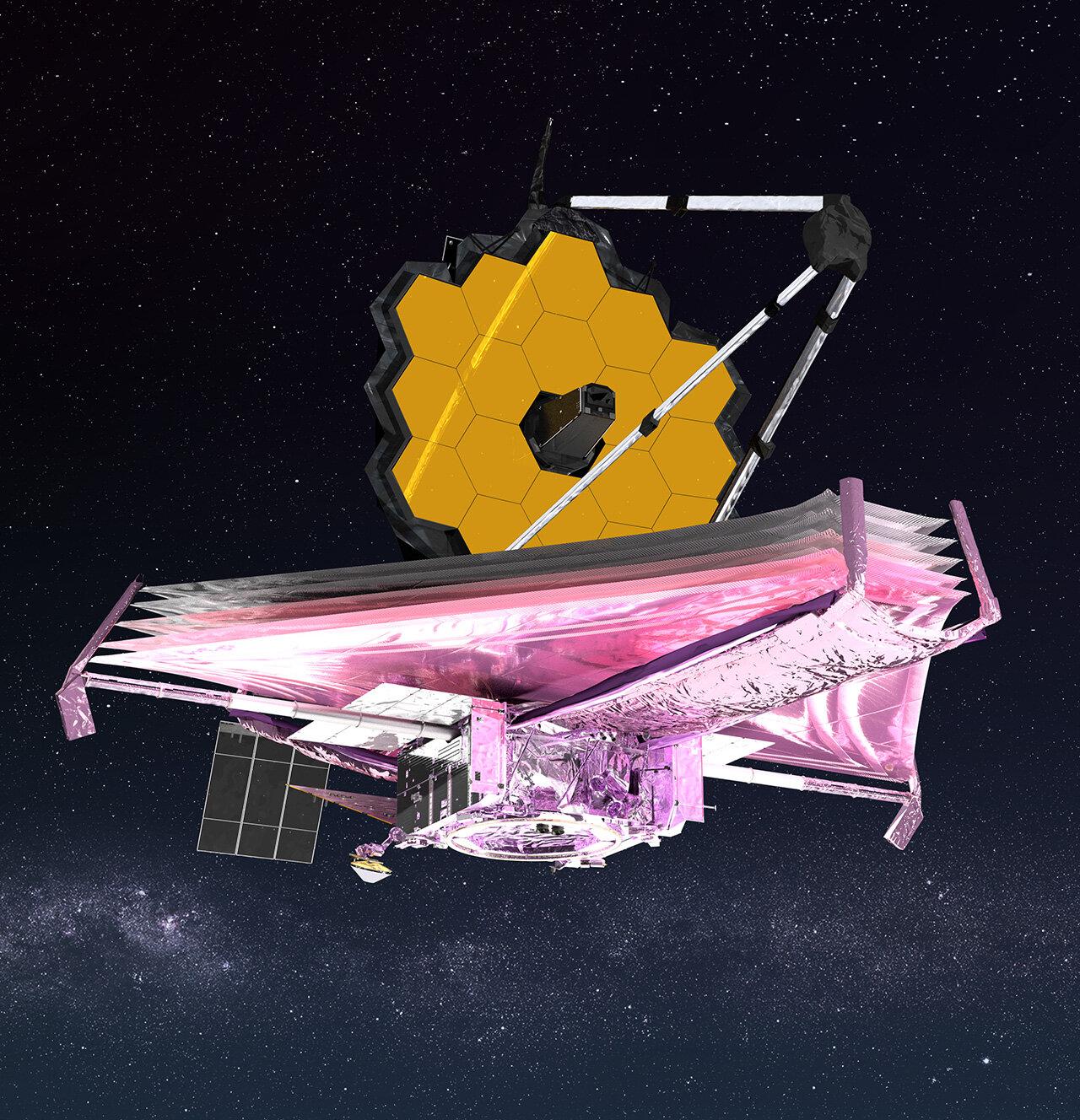

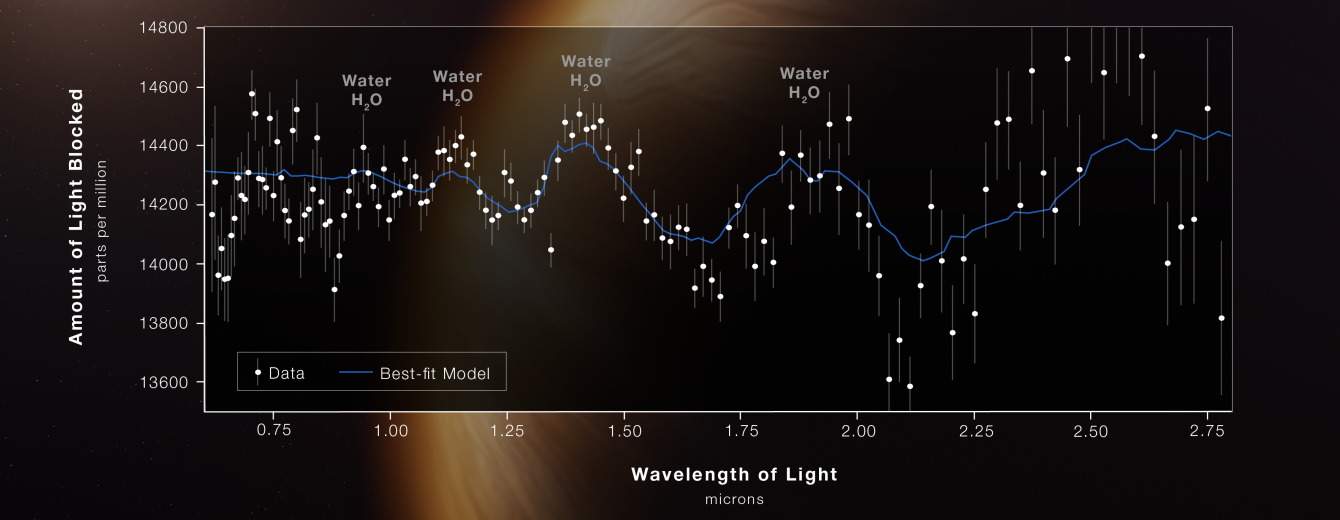

But that could be changing! We can, occasionally, get a glimpse of what sorts of things might be in an exoplanet’s atmosphere. And back last summer, when they released the first images from the James Webb Space Telescope and the astronomy world lost their collective minds, they also released a much less visually appealing but much more exciting (for me) graph that showcased the presence of water in the atmosphere of the exo-gas giant WASP-96 b. Webb has done this a few more times since then, and recently was able to provide some insight into the atmosphere of a rocky world.

This is HUGE. The ability to figure out exoplanet atmospheres is the big step we’ve been waiting for. It will allow us to look at rocky, habitable zone worlds and see if there’s a chance they could have liquid water on their surfaces. It would mean we would finally have the ability to say for certain whether or not a planet can be called “Earth-like” and not just “Earth-sized” (and here’s where I climb up on my soapbox for a moment: news sites often refer to exoplanet discoveries as being “Earth-like” when what they really mean is “Earth-sized”. The more you know).

So we might get to the place where we could say if an exoplanet would be habitable within the next several years, if we keep our fingers crossed. But the question was whether any of them could be more habitable than the Earth, and that’s trickier to figure out. You may have picked up that, even if we’re starting to be able to figure out finer details, we’re still dealing with pretty broad strokes here. Detecting liquid water is one thing. Detecting nuances in surface temperatures, how intense the seasonal changes are, what kinds of things might be growing on the surface—that may still be a while.

But we know something doesn’t have to be more habitable than Earth to have life on it—life on Earth developed when the planet was a much less pleasant place than it is now, and being just as habitable as it is hasn’t done us any harm. That said, if we can find a planet that is always like New England on a pleasant autumn day, sign me up for the first spaceship.

Of course, our dear Question Asker also asked about planetary quirks, specifically mentioning the quirk of Earth’s solar eclipses. It is a delightful cosmic coincidence that our Moon and our Sun, despite being such different sizes, are the right distances from us to appear about the same size in the sky, enabling the Moon to occasionally completely block the Sun while still allowing the solar corona to be visible. Nowhere else in our Solar System will you get a solar eclipse like on Earth.

As to whether this particular quirk is repeated on any of the exoplanets we’ve found, the answer is another resounding “we don’t know”. We’ve never found a confirmed exomoon. Yet. Give it a little time. We have found some other interesting planetary quirks out there though:

- WASP-76 b is a world with a daytime side so hot that any iron on this rocky world would vaporize. The nighttime side is also extremely hot, but cool enough for iron to turn from a vapor to a liquid, so it is suspected that this world may have iron rain.

- OGLE-2016-BLG-1928 is the smallest known of a class of planets known as rogue planets—which means this plant isn’t orbiting a star, but is drifting through space on its own.

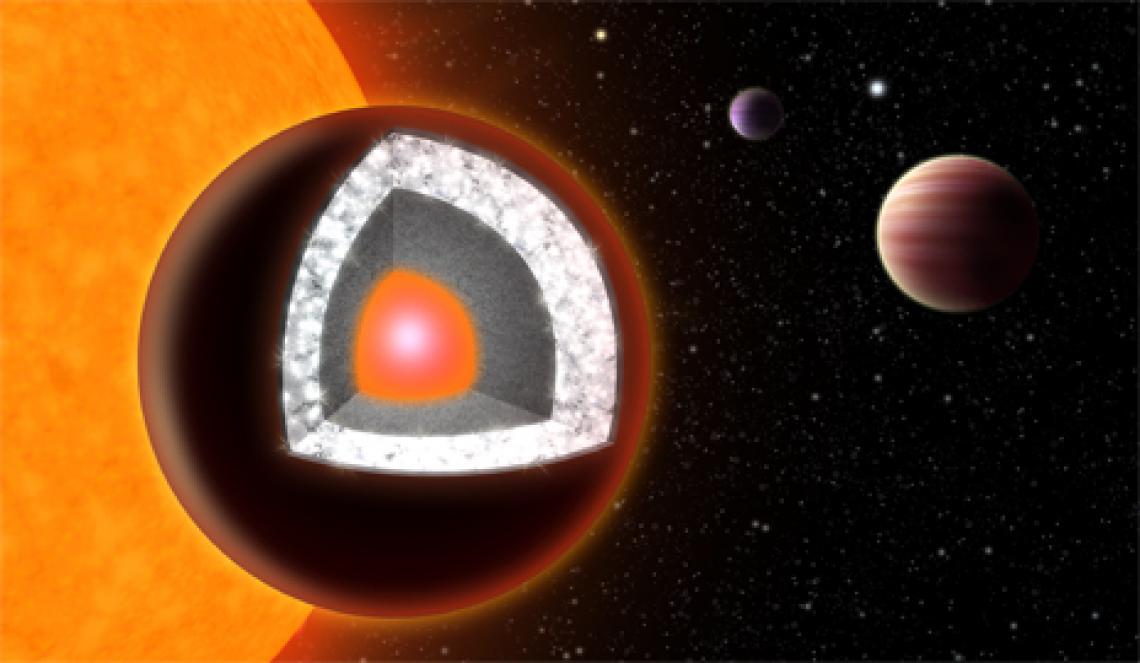

- 55 Cancri e is less than twice the radius of Earth, but is much, much more massive. That means it must be made of something pretty dense. One theory is that a lot of its insides are made up of compressed carbon in the form of diamond and graphite—making this a potentially very expensive planet.

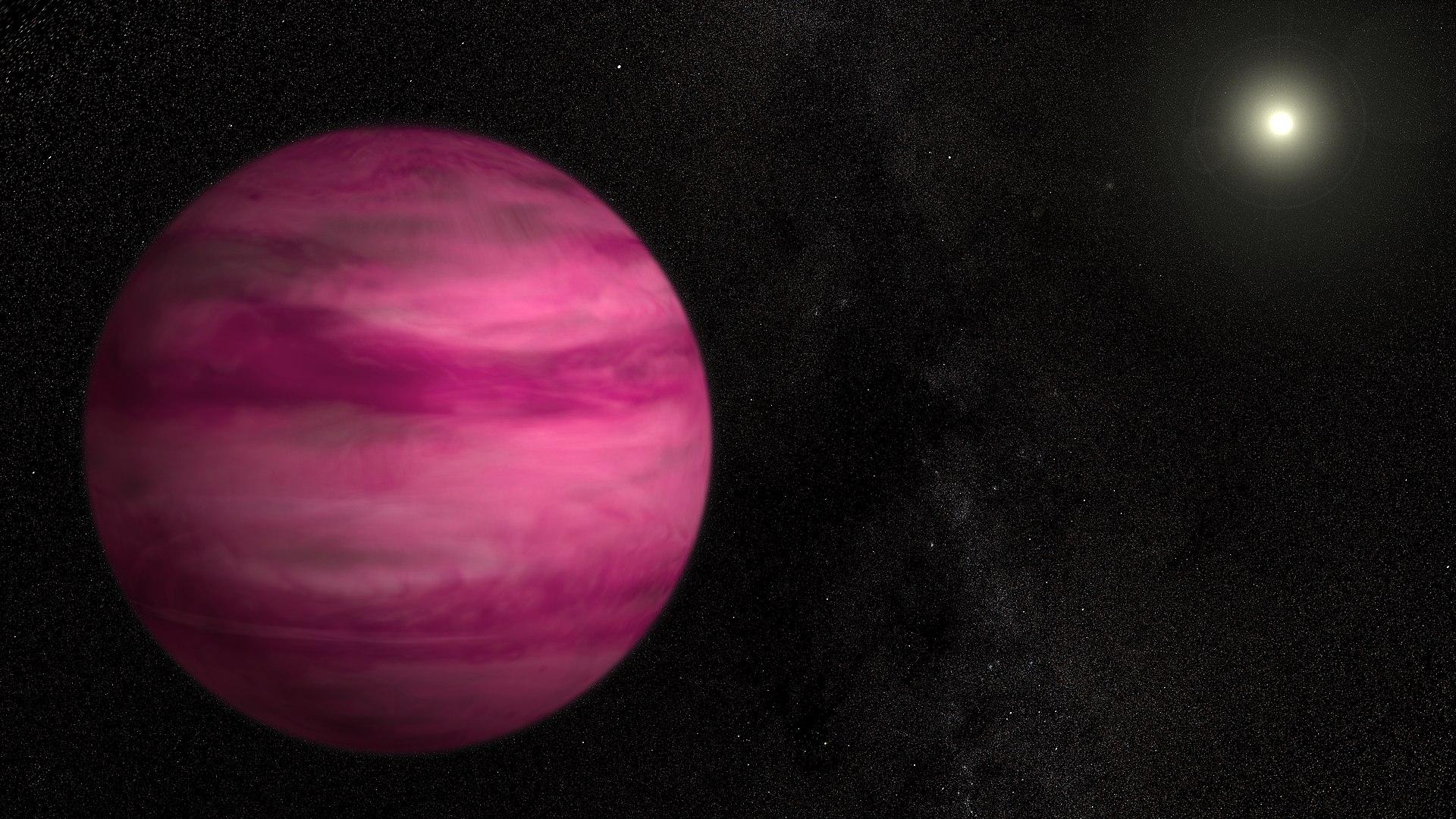

- GJ 504 b is pink. Or, well, magenta if we want to be specific. This planet is suspected to still be glowing from its birth, giving it a glowing pinkish color.

- WASP 12 b is a gas giant that is shaped like a football. Or a rugby ball. Or an egg. Whatever your favorite vaguely ovoid object is. This shape probably comes from the gases in the planet’s atmosphere being pulled towards and consumed by its star.

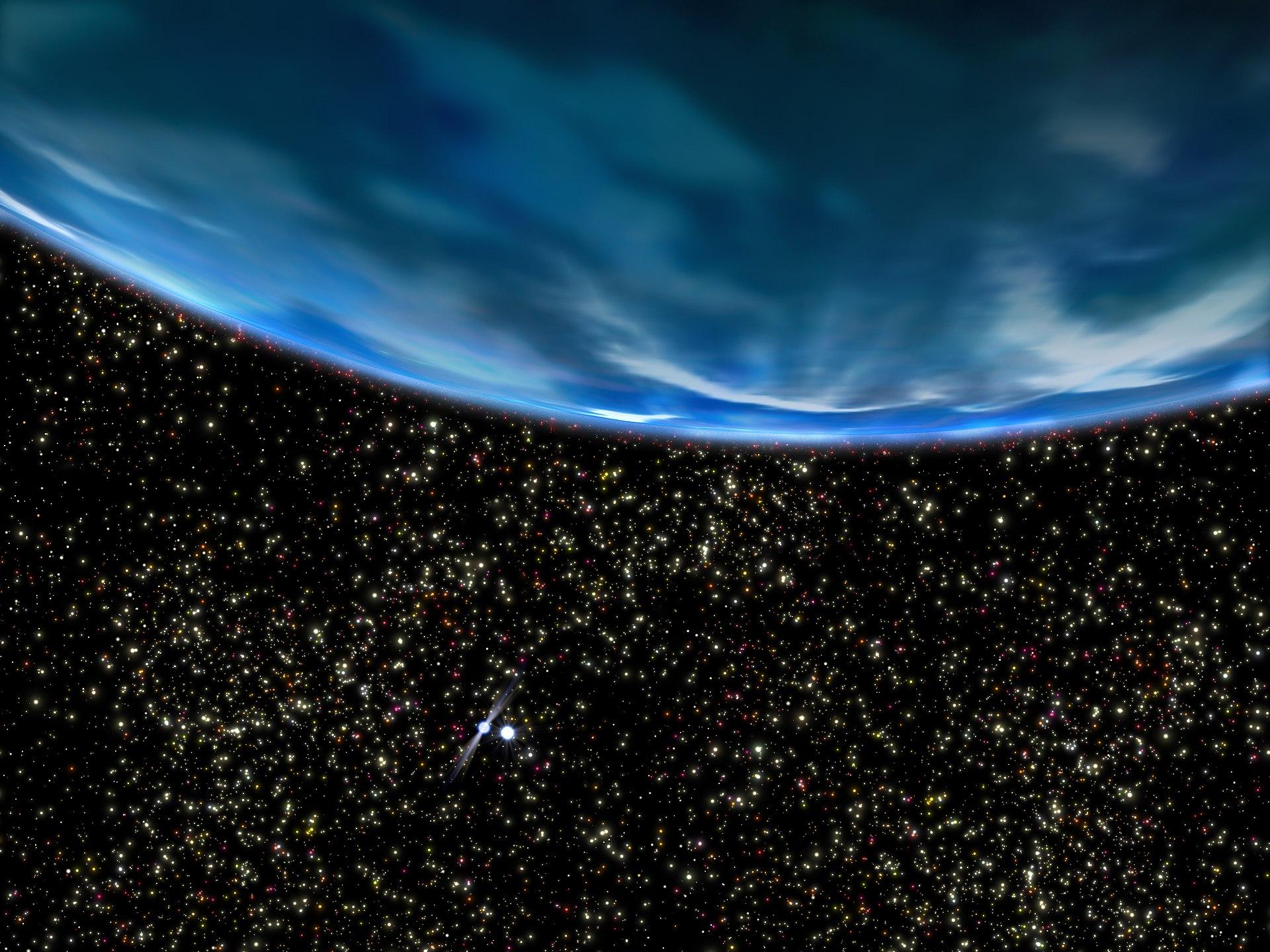

- PSR B1620-26 b is old. Very, very old. 12.7 billion years old. This planet isn’t actually orbiting a star, it’s orbiting a pair of stellar corpses, a white dwarf and a pulsar. The thinking is that this planet formed around the white dwarf when it was still a star and survived the star’s death, remaining bound to the white dwarf. Then, at some point the white dwarf drifted close to the pulsar (which formed when a very large star exploded in a supernova) and they began to orbit each other, sharing the planet between them. This planet’s extreme age has earned it the unofficial nickname “Methuselah”.

Arguably none of those quirks are quite as fun as our Earth’s ability to showcase total solar eclipses, but then I’m a biased Earthling, so maybe I shouldn’t talk.

So. That was an incredibly long-winded way of responding to a question whose answer can simply be boiled down to “we don’t know”. But exoplanet science is, in my personal opinion, one of the coolest fields of astronomy, and certainly one of the fastest-growing and fastest-changing. So this question innocently tapped into a wellspring of fascinating topics, so really it’s not my fault.

(That’s a lie, it’s definitely my fault. Sorry.)

(That’s a lie, I’m not sorry at all.)